This article is a guest contribution from Industry Expert Alejandro Aispuro. Alejandro is an award winning spirit maker with over 10 years of experience in natural fermentations, recipe development, blending, and sensory analysis of mezcal, whisky and other distilled spirits. He has been recognized as a whisky-maker and master blender, but his story began with mezcal and agave spirits, in which he continues to be involved and contribute.

In the making of mezcal and other agave spirits, fermentation is the quietest of processes. No roaring fire, no splashing still—just a slow bubbling, a deepening of aromas, a transformation underway beneath a veil of froth and fibre. And yet, this stage is where some of the spirit’s most distinctive characteristics are born.

Whether working with cultivated Espadín or wild Tepeztate, whether fermenting in wooden vats or clay ollas, the choices made—and the microorganisms involved—during fermentation shape much of what we later detect in the glass. Fermentation deepens and reshapes the agave’s existing flavour, aroma, texture, and sense of place—qualities already present in the raw material, but transformed through microbial and material interplay.

From Roasted Agave to Microbial Playground

Once the agave piñas are cooked and shredded, they become fertile ground for wild yeasts and bacteria. In traditional mezcal production, this fermentation is entirely spontaneous. There are no lab-grown yeasts or sealed vats—only ambient microbes from the palenque and the agave itself, interacting with the substrate.

The fermentation vessel plays a critical role. Wooden vats made of pine or oak, porous clay pots, and even cowhide containers each foster their own microbial habitats. These materials aren’t passive; they breathe, absorb, and host life, subtly shifting the trajectory of the fermentation and the resulting profile of the spirit.

The duration of fermentation varies—typically from three to twelve days—depending on environmental temperature, agave sugar content, and microbial dynamics. As fermentation progresses, the must emits a shifting bouquet of aromas: sour fruit, crushed herbs, warming alcohol, and at times a tang of vinegar or even cheese. These are more than signs of sugar conversion—they’re the first hints of what the mezcal’s defining and final flavour will be.

Aroma and Texture: Building Complexity

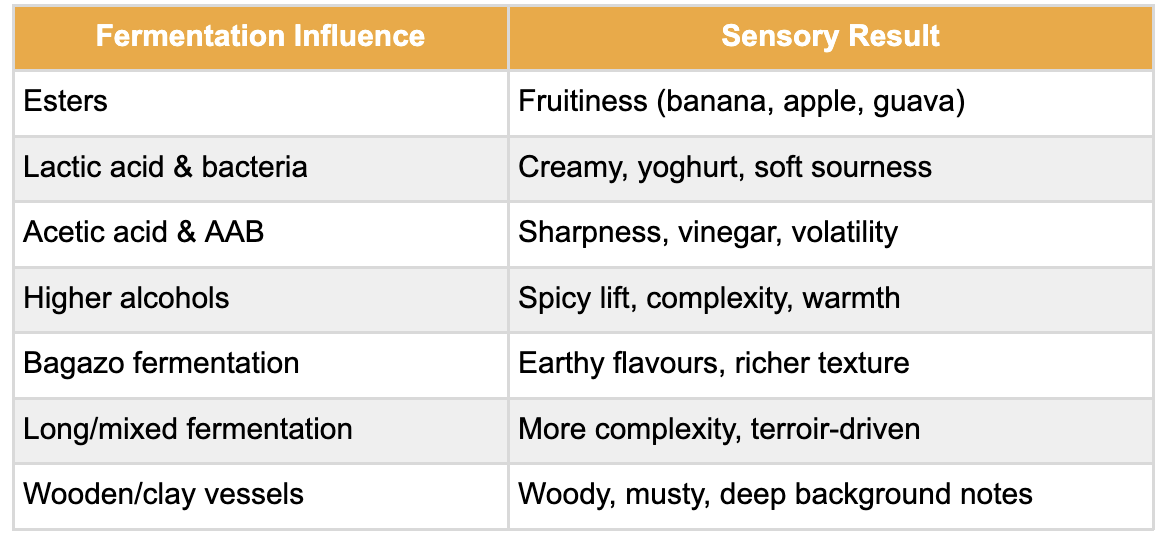

Fermentation doesn’t merely produce alcohol; it crafts the architecture of flavour. Esters formed by yeasts and bacteria bring out fruitiness—banana, apple, or even guava-like notes. Lactic acid bacteria lend creamy, yoghurty softness, while acetic acid brings bright, sometimes volatile sharpness. Higher alcohols add structure and lift, while volatile phenols and other compounds formed through microbial stress and fibre contact, or acquired from the cooking process, may contribute earthy, smoky, or spicy tones.

Texture, too, begins to take shape. Fermentations rich in glycerol, or those that involve fibrous bagazo, often result in a spirit that feels fuller, creamier, or more grippy on the palate. The inclusion of fibres in fermentation or distillation doesn’t just extract more sugars—it adds a tangible physicality to the spirit’s final feel.

The following table gives a snapshot of how key fermentation influences are reflected in the sensory profile of the resulting mezcal:

Agave Variety: A Foundation for Fermentation

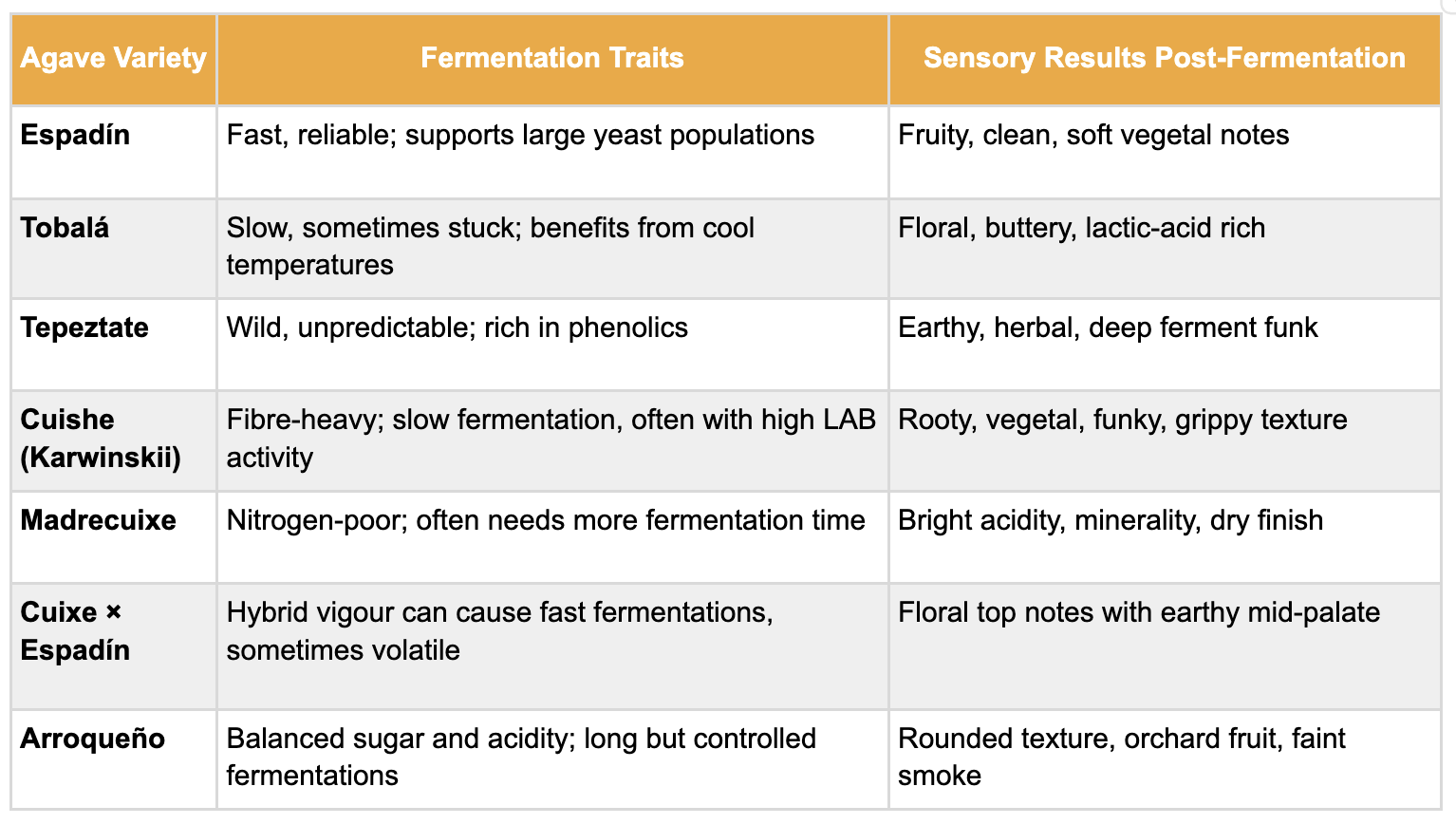

Different agave species set the stage for very different fermentations. Espadín tends to ferment reliably and quickly, producing fruity, approachable distillates. In contrast, Tobalá’s lower sugar content and rich aromatic precursors require patience and can benefit from cooler, longer fermentations that highlight floral and lactic nuances.

Karwinskii types like Cuishe and Barril bring dense fibres and often low nitrogen, slowing fermentation and inviting microbial stress. This can lead to earthy, vegetal complexity and a textured mouthfeel. Tepeztate, one of the more unpredictable agaves to work with, offers fermentations that are wild, phenolic, and hauntingly complex—though not without risk.

Below is a brief comparison of fermentation traits and their sensory impact across some common agave varieties:

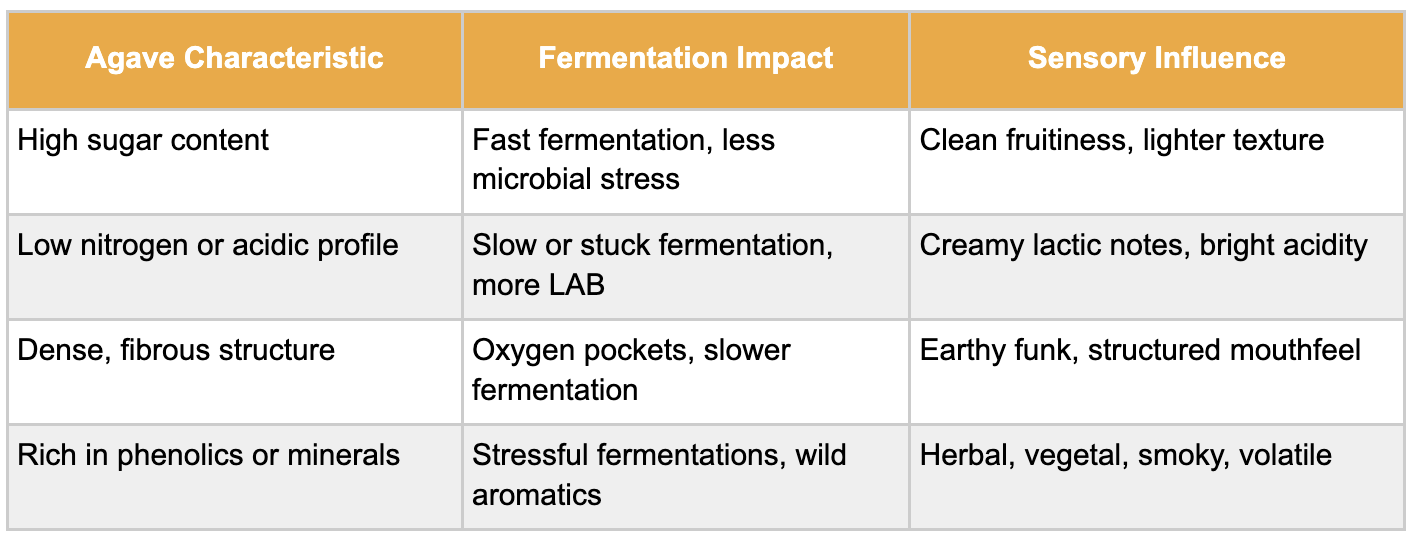

Each variety, in essence, not only provides a canvas of sugars and minerals but also influences the microbial succession, fermentation speed, and eventual flavour development. The spirit carries with it traces of these choices—some obvious, others only perceptible after quiet contemplation.

For an even broader view of how agave characteristics influence fermentation and sensory outcome, consider the following table:

Fermentation as Expression

Fermentation is far more than a technical step. It is a space of expression and tension, where environment, raw material, and microbial life all converge. For the mezcalero, it’s not something to control so much as to collaborate with—listening, adjusting, sometimes waiting, and always respecting the invisible forces at play.

In the end, it’s this stage that allows a spirit to speak in layers: not just cooked agave and smoke, but fruit, earth, air, time, and touch. And for those who sip with attention, fermentation offers a thread that leads back not only to the maker but to the microbes, the fibres, the vessels, and the agave itself.